A Few Words on Representation Learning

[machine-learning deep-learning representation-learning self-supervised-learning contrastive-learning

Source Image: Introducing Activation Atlases

Introduction

In the last two decades, the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has seen substantial development in research and industrial applications. Machine learning algorithms such as Logistic Regression and Naive Bayes can recognize patterns from a set of features and solve problems that seemed otherwise impossible to be solved by hard-coding knowledge into expert systems. These shallow learning algorithms can perform relatively complex tasks such as product recommendation or learn to distinguish between spam from not-spam emails.

More interesting,

the performance of these shallow machine learning algorithms massively depends on the representations they receive as input.

For instance, if we decide to build a spam email detector using Naive Bayes, passing a large body of raw unstructured email data to the classifier will not help.

Instead, we need to find a different way to represent the text before feeding it to the classifier.

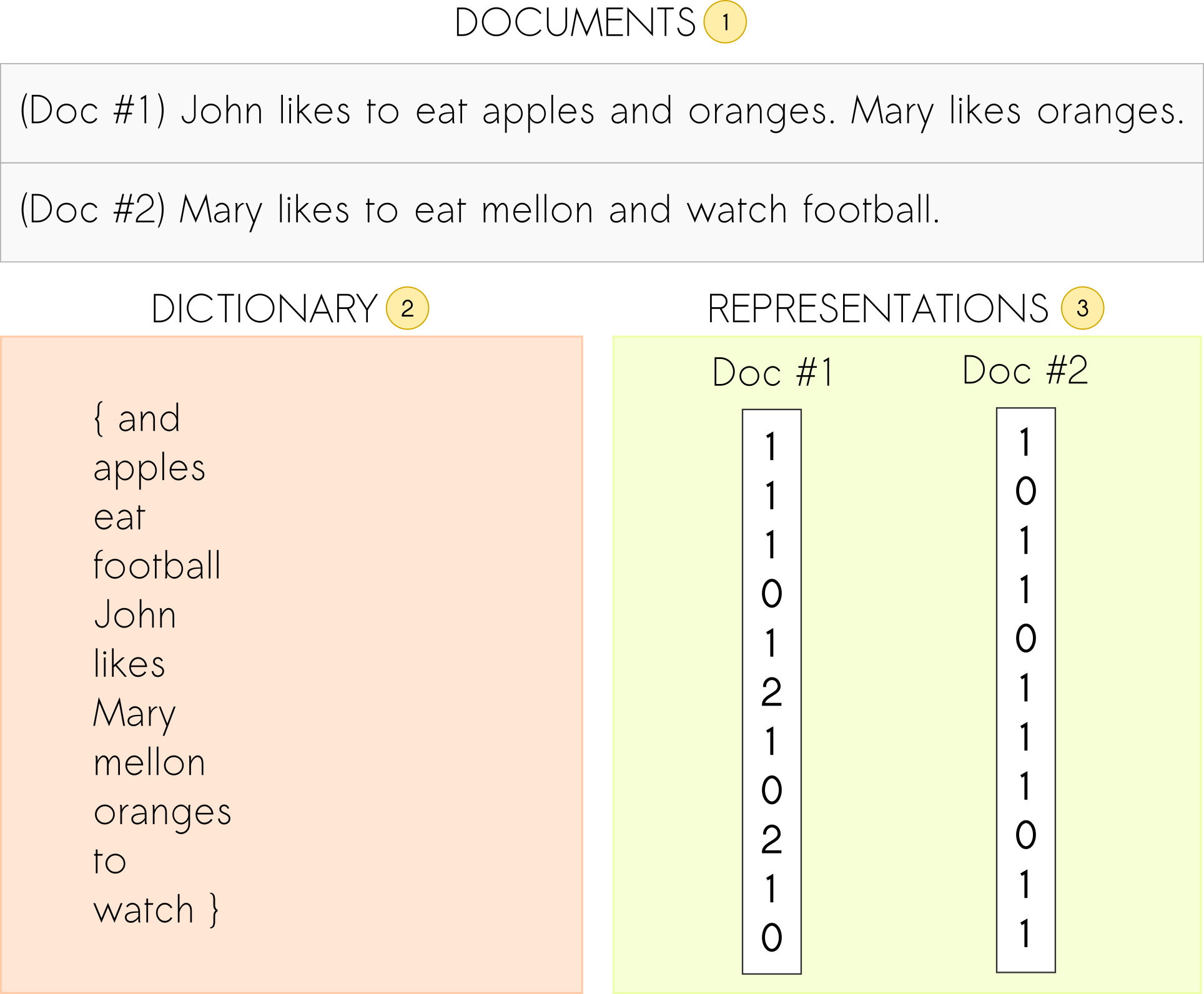

Notably, one commonly used text representation for this kind of application is the bag-of-words model.

The idea is to represent the text so that the importance of each word is easily captured.

Namely, the term frequency of each word (Figure 1), which represents the number of times a word appears in the text, is a popular text representation that can be used to train the spam filtering model.

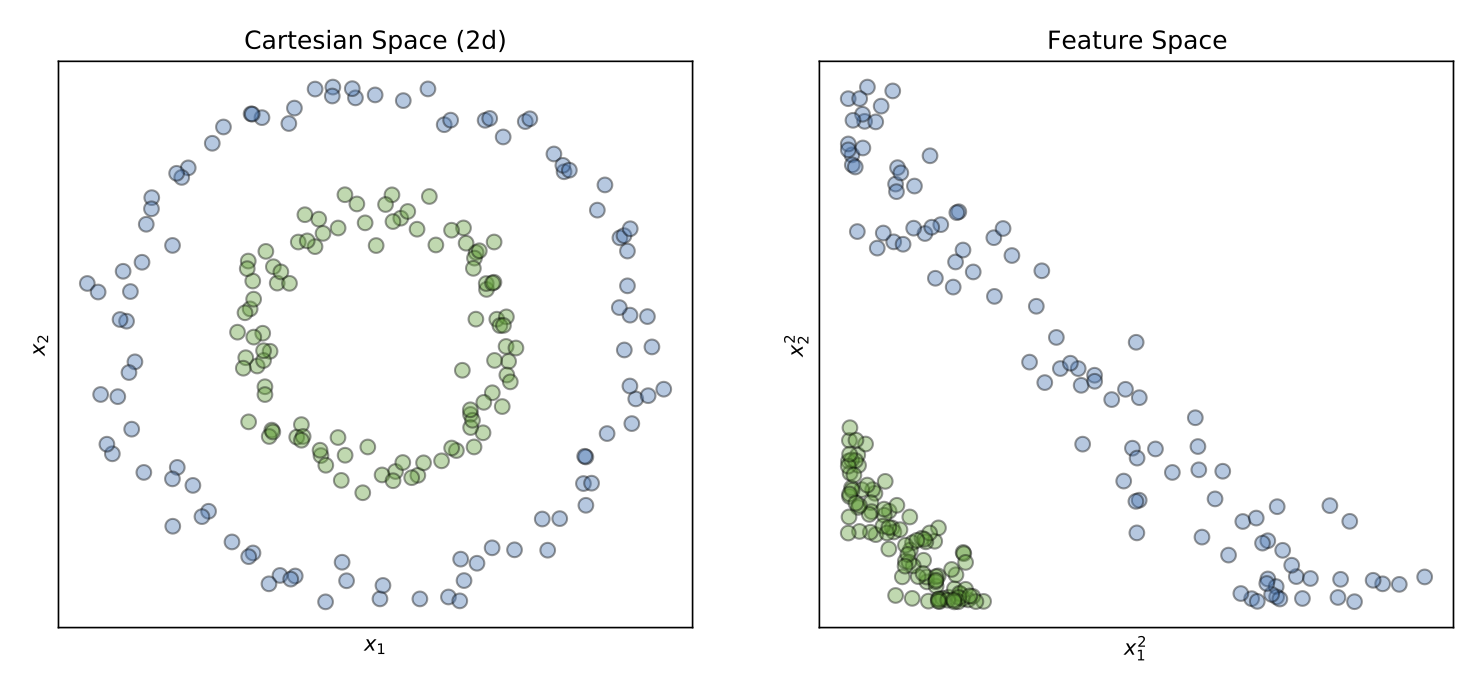

We can see the power of good representations for training machine learning models by looking at Figure 2. In this example, we might want to use a machine learning model such as Logistic Regression to find a linear separation, a line in 2D, between the blue and green circles. However, it is straightforward to see that a model that learns linear boundaries will not succeed in such an example because there is no way to separate the two classes using a line in this current state of the data. Luckily, if we change the input representation so that instead of passing the raw data, we pass in the square magnitude of the values, we will see that the data landscape will change completely, and a linear separation between the two groups becomes evident in the feature space. Indeed, representations matter.

Nevertheless, it is not straightforward to know beforehand how to change the data representation in such a way so that linear separations in the feature space become evident. Different features often have different properties that may or may not be suited to solve a given task. Take the bag-of-words term frequency features as an example. These features focus on the number of occurrences of a word in the text but discard information such as grammar and word order. For other natural language problems, where the semantic relationship between words is necessary, the grammar and the order in which words appear in the text may be critical to solving that particular task.

That is why the process of hand-designing features is considered such a challenging problem. For instance, imagine we want to build a car detector. We know that cars have some primary characteristics that make them different from other objects. Such components, one might argue, is the presence of wheels. In this scenario, to build a car classifier, we need to have a way to represent the wheels of various types of cars. That is where the problem becomes complicated. After all, how could we create a wheel-detector that could generalize among all types of existing wheels and be robust to so many combinations of light, shape, and size distortions?

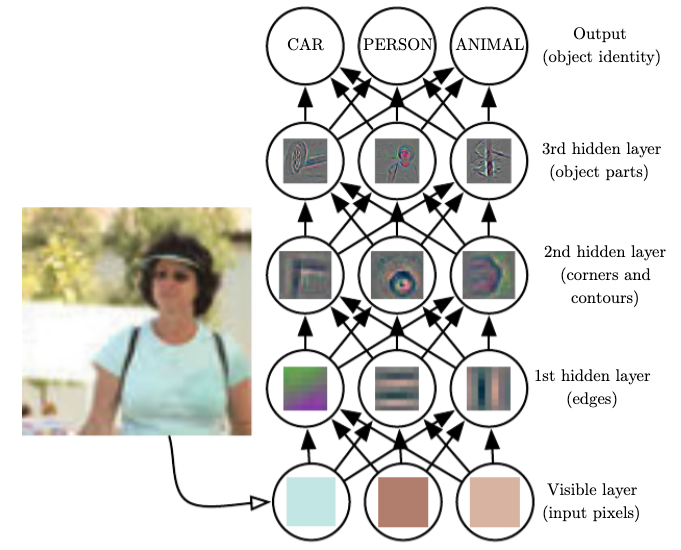

That is where deep neural networks make a difference. With deep learning, we do not need to care about how to manually specify a wheel detector so that it can be robust to all types of existing wheels. Instead, by composing a series of linear and non-linear transformations in a hierarchical pattern, deep neural networks have the power to learn suitable representations by combining simple concepts to derive complex structures. In a nutshell, a classical supervised computer vision classifier would take raw data as input, and each layer iteratively refines the features from the previous layers. Thus, the neurons of the first layers may learn programs that can detect edges and contours from the high-frequency input, and as the features traverse the hierarchy of layers, the subsequent neurons combine the pre-existing knowledge to learn more complex programs that can detect object parts. Lastly, we can use these refined representations and learn a linear classifier to map the inputs to a set of finite classes.

Image Source: Deep Learning

From this perspective, deep neural networks are representation learning models. At a high-level, a typical supervised neural network has two components, (1) an encoder and (2) a linear classifier. The encoder transforms the input data and projects it to a different subspace. Then, the low-level representation (from the encoder) is passed to the linear classifier that draws linear boundaries separating the classes.

However, instead of solving a task by mapping representations to targets (which a classical classifier would do), representation learning aims to map representations to other representations. These learned representations are often dense, compact, and can generalize to similar data modalities. In other words, these representations can transfer well to other tasks and have been the principal method to solve problems in which data annotations are hard or even impossible to get.

The Story so Far

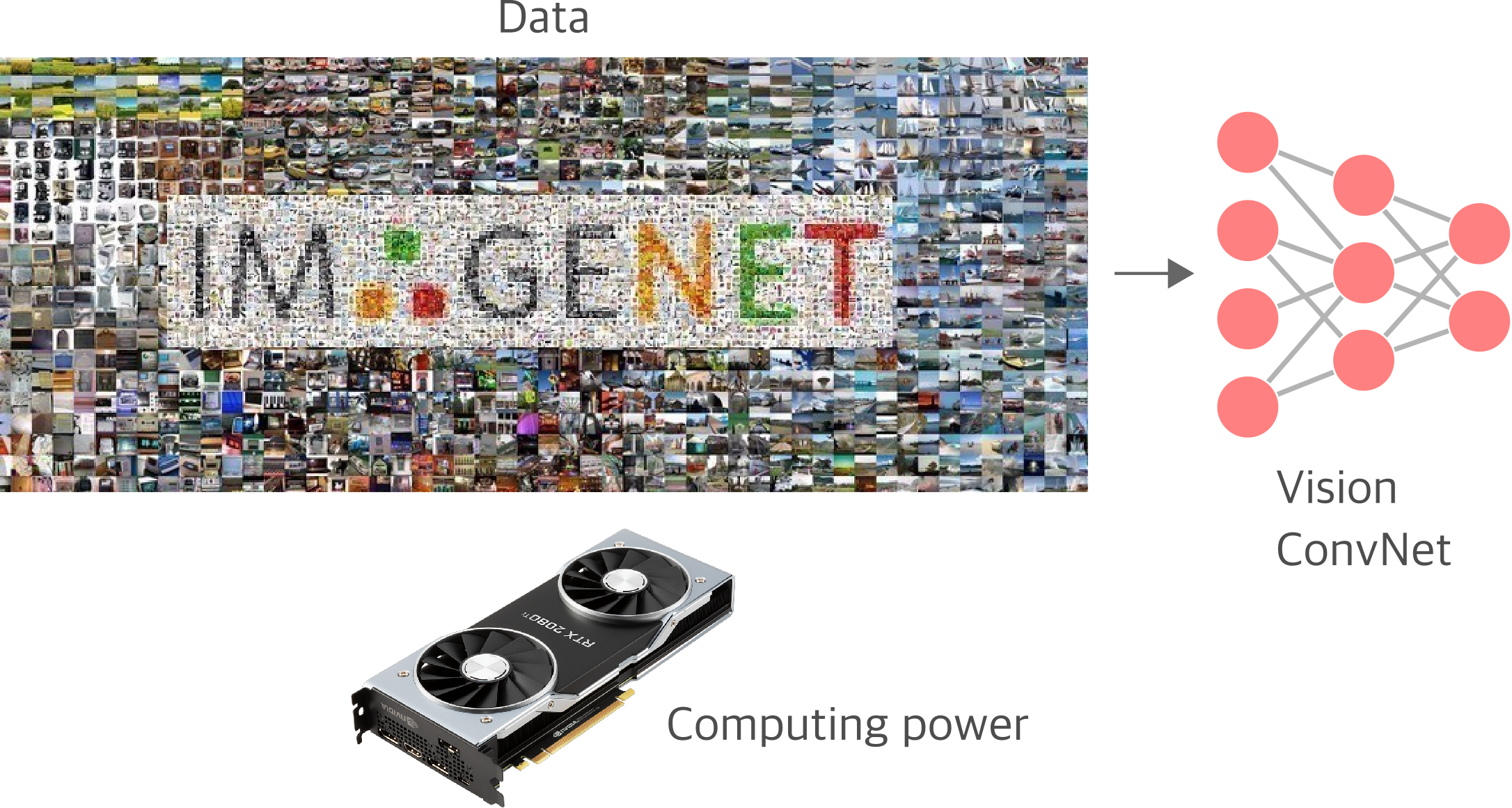

Throughout recent years, supervised learning has been the leading and successful recipe for training deep neural networks. The availability of large, and most importantly, annotated datasets such as the ImageNet, allowed researchers to train deep neural network models and learn representations in terms of a hierarch of concepts. These representations not only solve the task at hand, image classification in this case, but because of their generalization properties, they can also be used as a good starting point to learn different downstream tasks such as object detection, segmentation, pose estimation and so on.

The recipe is simple, take a large annotated vision corpora, train a Convolutional Neural Network, then transfer its knowledge to solve a second task that usually does not have sufficient labels to train a deep network from scratch. This concept, called transfer learning, has been used successfully in many different domains to solve numerous tasks and has been immensely used in commercial applications.

The main limiting factor to scale this recipe lies in the acquisition of annotated data. To have an idea, the ImageNet dataset, which is a standard dataset among Computer Vision researchers, contains 14 million images with roughly 22 million concepts. However, if we compare ImageNet with the set of all available internet images, ImageNet is down by approximately five orders of magnitude.

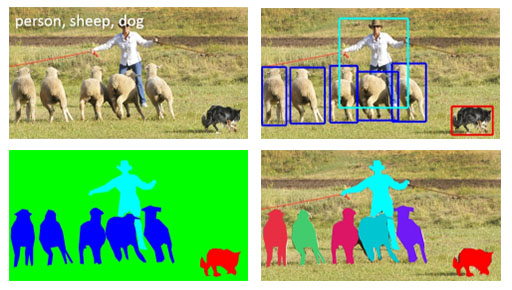

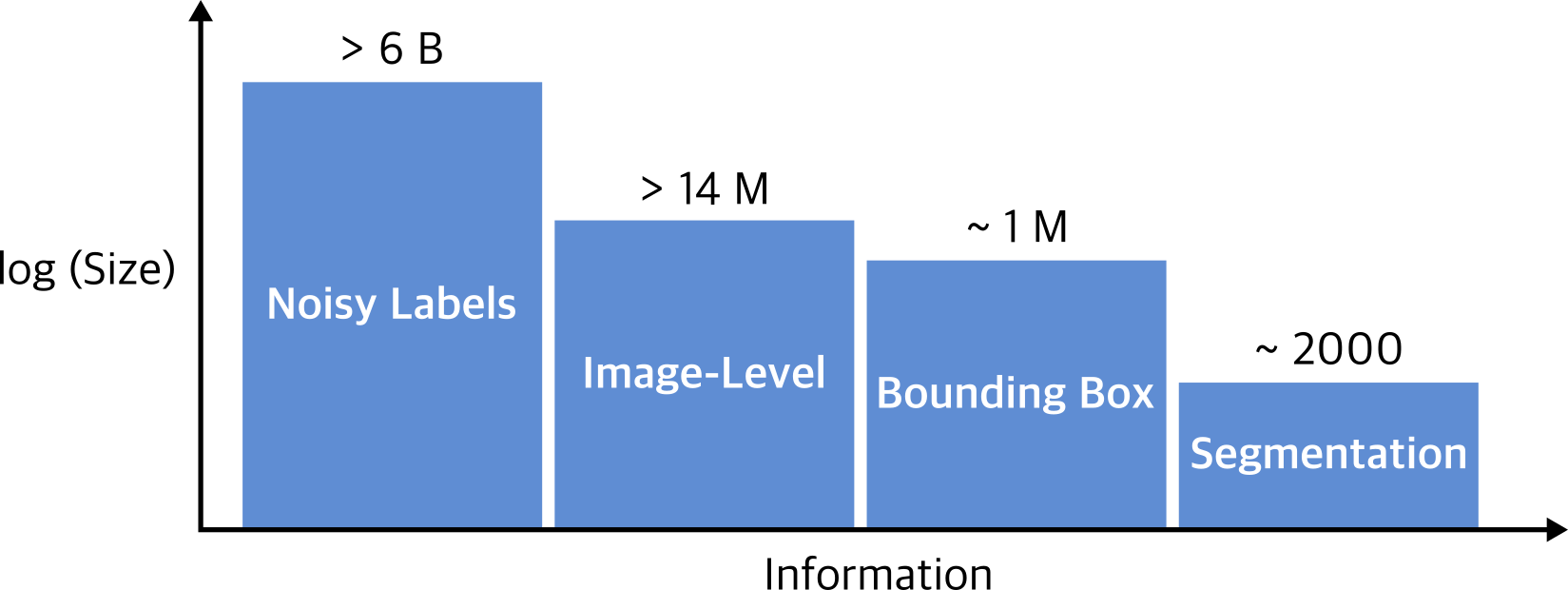

Besides, if we look at the computer vision dataset landscape, the number of available annotated samples reduces drastically depending on the task at hand. Suppose we consider only the most popular computer vision tasks such as object classification, detection, and segmentation (Figure 5). In this scenario, as the level of prediction becomes more complex (from whole-image labels to pixel-level annotations), the number of labeled examples decreases substantially (Figure 6). That is why most of the solutions to object detection and segmentation always take ImageNet pre-trained networks as starting points for optimization.

Image Source: Visual Learning with Weak Supervision.

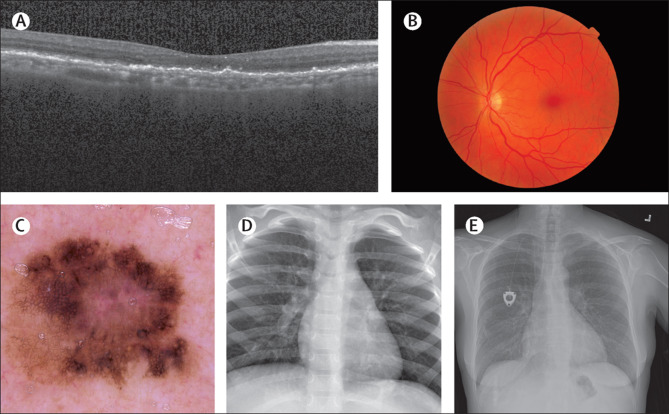

However, for problems where there is a significant change in the domain, ImageNet pre-trained models might not be the ideal solution. That might be the case for numerous applications in health care, such as classification and detection of breast cancer metastases in whole-slide images. In such applications, the set of curated annotated samples is minimal if compared to the set of raw non-annotated data. The process of annotating such records usually requires hours of specialized expert pathologists who need years of training to be capable of performing such a job—in situations like this, annotating a large dataset becomes prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

Also, the rate at which humans annotate data cannot scale to the volume of the data we generate. Put it in another way, if we do not know the task to be optimized a priory, it might be very complicated and expensive to prepare a sizeable supervised dataset required by deep learning training.

All of these examples highlight the importance of learning generalizable representations from non-annotated data. Many research areas, including semi-supervised, weakly-supervised, and more recently, self-supervised learning, try to learn representations that can be transferred to new tasks using just a few or not using annotated examples at all.

Semi-supervised learning aims to combine the benefits of having a few annotated observations with a much larger dataset of non-annotated examples. On the other hand, weakly supervised learning explores a large amount of noisy, and most of the time, imprecise labels as supervised signals. Finally, self-supervised learning is all about learning good models of the world without explicit supervised signals. It involves solving pretext tasks from which annotations derive from the data or its properties. By optimizing these pretext tasks, the network learns useful representations that can be easily transferred to learn downstream tasks in a data efficient way.

Deep Unsupervised Representation Learning

So far, we have been discussing how deep neural networks can learn generalizable representations by solving supervised tasks. In general, we can take advantage of the knowledge a neural network has gained from task A (trained with a lot of annotated data) and apply that knowledge to learn a separate task B (usually scarce of annotations). The problem here is that we still rely on having a lot of annotated data to learn the representations in the first place. Also, depending on the nature of the task, annotating data can be really difficult or even impossible to do. But what if we could learn equally good (or even better) representations by learning tasks in an unsupervised (label-free) way?

Deep unsupervised representation learning seeks to learn a rich set of useful features from unlabeled data. The hope is that these representations will improve the performance of many downstream tasks and reduce the necessity of human annotations every time we seek to learn a new task. Specifically, in Computer Vision (CV), unsupervised representation learning is one of the foremost, long-standing class of problems that pose significant challenges to many researchers worldwide. As computing power rises more and more, and data continues to be ubiquitously captured through multiple sensors, the need to create algorithms capable of extracting richer patterns from raw data in a label-free way has never been so present.

In recent years, deep unsupervised representation learning has gained much attention because of the latest breakthroughs in Natural Language Processing (NLP). The successes of BERT and GPT, both deep learning-based models that do not require manual annotations in their training pipelines, has inspired a new generation of algorithms that made their way to Computer Vision applications. More specifically, the recently developed field of self-supervised learning, which takes advantage of the supervision encoded in the data, is the main driver behind the latest successes in unsupervised representation learning for CV and NLP applications.

Let us take Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers or BERT as an example. BERT is a deep unsupervised language representation model that learns contextual representations from unstructured text. Context-free models such as word2vec and GloVe learn word embeddings without taking into consideration the context in which words appear. This is a limitation because a lot of words express different meanings depending on the context they are used. Words like “bank” for instance, may show up in a financial-related context such as “bank account” or it may be used to describe the edges of a river. Differently, BERT learns representations based on the context in which words appear. As a result, BERT is able to learn richer semantically meaningful representations that capture different meanings of words depending on their context.

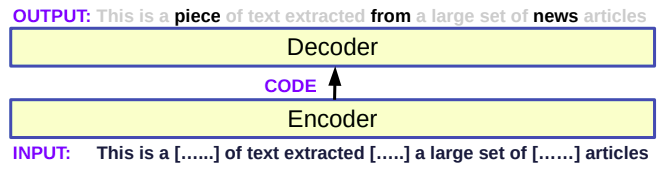

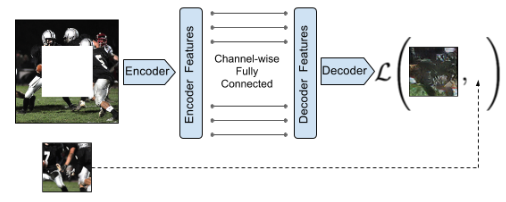

Moreover, BERT is optimized by solving a particular kind of self-supervised task that does not require manually annotated data. Namely, during training, a percentage of randomly chosen tokens are masked from the input sentence before going through the Transformer encoder. The encoder maps the input sentence to a series of embedding vectors (one for each word in the sentence). These vectors are subsequently passed through a softmax layer that computes probabilities over the whole vocabulary so that the most likely words get a higher chance of being picked. In other words, it is a filling in the blank task where BERT aims to reconstruct the corrupted input signal from the partially available context.

This particular task is called masked auto-encoder, and it has been shown to work well in situations where we have a discrete probability space.

Nevertheless, the most important characteristic of a system such as BERT is that, after training, we can fine-tune the BERT parameters on different downstream tasks that do not have much training data available, and we will achieve substantial accuracy improvements compared to training the system from scratch. And this is specifically important because data-annotation is a significant bottleneck in deep neural network training.

Clustering and Self-supervised Learning

Over the years, clustering techniques have been the main class of methods to learn structure from non-annotated data. Classic methods, e.g. K-Means, optimize a distance metric as a proxy to group similar concepts, such as images, around a common centroid. Recent methods such as Deep Clustering for Unsupervised Learning of Visual Features by Caron et al. and Prototypical Contrastive Learning of Unsupervised Representations by Li et al. have attempted to combine clustering with deep neural networks as a way of learning good representations from unstructured data in an unsupervised way. These results suggest that combining clustering methods with self-supervised pretext tasks is a prominent technique.

On the other hand, self-supervised learning is an approach to unsupervised learning that is concerned with learning semantically meaningful features from unlabeled data. The first approach to self-supervised learning regards devising a predictive task that can be solved by only exploring the characteristics present in the data. This subtask, or pretext task, acts as a proxy that makes the network learn useful representations that can be used to ease the process of learning a different downstream tasks.

While classic unsupervised methods do not use any labels during training, most of the proposed pretext tasks use the same framework and loss functions as classic supervised learning algorithms. Therefore, self-supervised pretext tasks also require labels for optimization. However, the labels (or pseudo-labels) used to optimize these pretext tasks are derived from the data or its attributes alone.

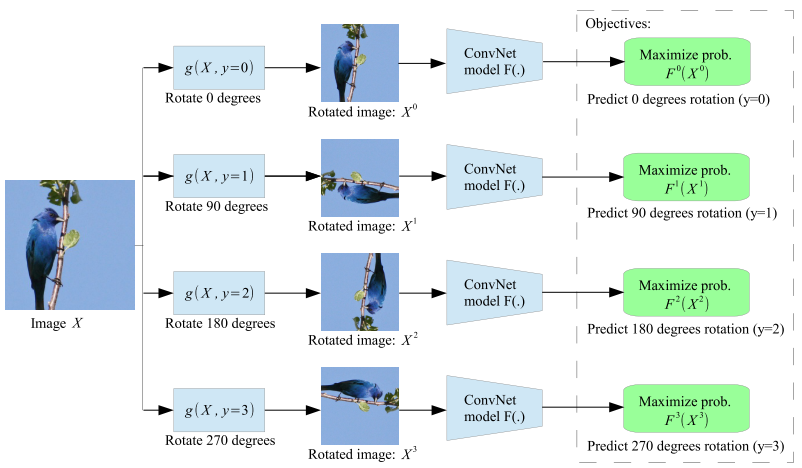

Image Source: Unsupervised Representation Learning by Predicting Image Rotations

In general, self-supervised pretext tasks consist of taking out some parts of the data and challenging the network to predict that missing part. It can be predicting the next word in the sentence based on the previous context or predicting the next frame of a video based on the preceding ones. In fact, such pretext tasks have seen massive success in NLP applications, mainly because text data is discrete. Hence, naively applying these same concepts to CV applications is hard because images are continuous, making the space of possible solutions much more complex.

Besides, creating self-supervised pretext tasks might resemble the process of hand-designing features for a classifier. It is not clear which pretext tasks work and why they work. Nevertheless, recent self-supervised learning methods have deviated to a general approach that involves a kind of instance discrimination pretext task combined with contrastive-based loss functions.

The general idea is to learn representations by approximating similar concepts while pushing apart different ones. As of this writing, contrastive learning methods hold state-of-the-art performance in unsupervised representation learning. In fact, the gap between supervised and unsupervised pre-training has never been that small, and for some downstream tasks, pre-training an encoder using self-supervised techniques is already better than supervised training.

In the next piece, we are going to explore the landscape of self-supervised learning methods. We will go deeper into some of the most successful implementations and discuss the current state of the field.

Thanks for reading!

Cite as:

@article{

silva2021reprlearning,

title={A Few Words on Representation Learning},

author={Silva, Thalles Santos},

journal={https://sthalles.github.io},

year={2021}

url={https://sthalles.github.io/a-few-words-on-representation-learning/}

}