Self-Supervised Learning and the Quest for Reducing Labeled Data in Deep Learning

[machine-learning deep-learning representation-learning self-supervised self-supervised-learning tensorflow pytorch

Introduction

There is one single thing that every Deep Learning practitioner agrees.

Deep learning models are data inefficient.

Let’s start by considering the popular task of classification in Computer Vision. Take the ImageNet database as an example. It contains 1.3 million images from 1000 different classes. For each one of these images, there is a single human-annotated label.

ImageNet was certainly one of the stepping stones for the current deep learning revival. Most of it started in 2012 with the AlexNet model by Krizhevsky et al. Here, ConvNets, for the first time, beat the current state-of-the-art model by a large margin. Among the competitors, it was the single ConvNet based solution. After that, ConvNets became ubiquitous.

Before deep learning, the ImageNet challenge has always been considered very difficult. Among the main reasons, its large variability stood out. Indeed, to build handcrafted features that could generalize among so many classes of dogs wasn’t easy.

However, with deep learning, we soon realized that what made ImageNet so hard was actually the secret ingredient to make deep learning so effective. And that is the abundance of data.

Nevertheless, after years of deep learning research, one thing became clear. The necessity of large databases for training accurate models became a very important concern. And this inefficiency becomes a bigger problem when human-annotated data is required.

Moreover, the problem with data is everywhere in current deep learning applications. Take DeepMind’s AlphaStar model as another example.

Source: AlphaStar: Mastering the Real-Time Strategy Game StarCraft II

AlphaStar is a deep learning system that uses supervised and reinforcement learning to play StarCraft II. During training, AlphaStar only sees raw image pixels from the game console. To train it, DeepMind researchers used a distributed strategy where they could train a huge population of agents in parallel. Each agent experienced at least 200 years of real-time StarCraft play (non-stop). AlphaStar was trained with similar constraints a professional player would have. And it was ranked above 99.8% of active players in the official game server — a huge success.

Despite all general-purpose techniques used to train the system, one thing was crucial to successfully build AlphaStar (or pretty much any other RL agent) — the availability of data. In fact, the best reinforcement learning algorithms require many (but many) trials to achieve human-level performance. And that goes directly opposite to the way we humans learn.

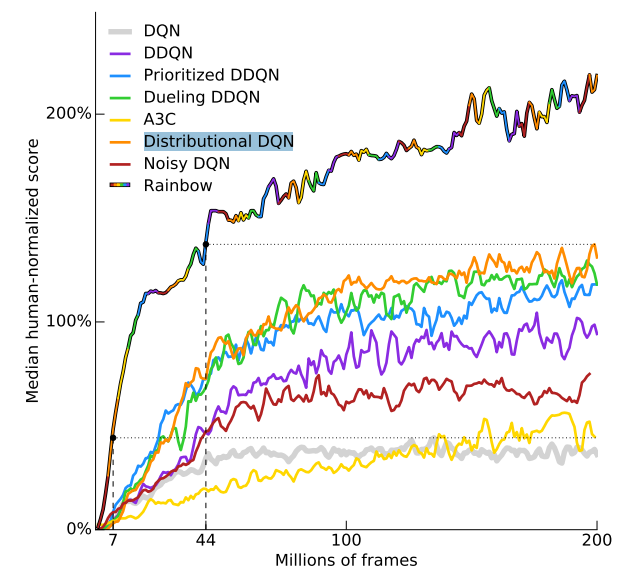

As a consequence, the great successes came on restricted and well-defined scenarios with massive amounts of available data. Take a look at this paper by DeepMind. The best RL methods need nearly 100 hours (10.8 Million frames) of non-stop playing to reach the same performance level a professional human would on a set of Atari Games. Despite recent improvements, this still seems too much.

Credits: Rainbow: Combining Improvements in Deep Reinforcement Learning

For more information on AlphaStar take a look at this short summary from THE BATCH.

I could bother you with some more examples, but I guess these 2 speak to the point I want to make.

Current deep learning is predicated on large-scale data. These systems work like a charm when their environment and constraints are met. However, they also fail catastrophically in some weird situations.

Let’s return to classification on ImageNet for a bit. To contextualize, the database has an estimated human error rate of 5.1%. On the other hand, the current state-of-the-art deep learning top-5 accuracy is around 1.8%. Thus, one could perfectly argue that deep learning is already better than humans on this task. But is it?

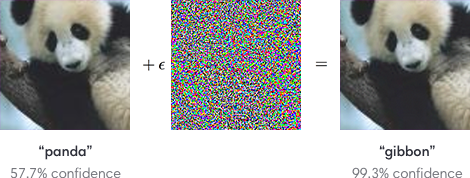

If that is the case, how can we explain such things?

Credits: Attacking Machine Learning with Adversarial Examples

These examples, that became very popular on the internet, are called adversarial examples. We can think of it as an optimization task designed to fool a machine learning model. The idea is simple:

How can we change an image previously classified as a “panda” so that the classifier thinks it is a “gibbon”?

We can simply think of it as input examples carefully designed to fool an ML model into making a classification mistake.

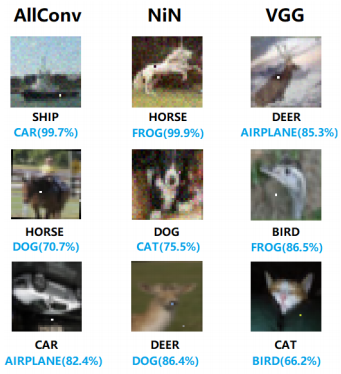

As we can see, the optimization is so effective that we can’t perceive (with naked eyes) the difference between the real (left) and the adversarial (right) images. Indeed, the noise, responsible for the misclassification, is not any type of known signal. Instead, it is carefully designed to explore the hidden biases in these models. Moreover, recent studies have shown that in some situations we only need to change 1 single pixel to completely fool the best deep-learning classifiers.

Credits: One Pixel Attack for Fooling Deep Neural Networks

At this point, we can see that the problems are starting to stack on top of each other. Not only do we need a lot of examples to learn a new task, but we also need to make sure that our models learn the right representations.

When we see deep learning systems fail like that, an interesting discussion arrives. Obviously, we humans do not get easily fooled by examples like these. But why is that?

One can argue that when we need to grasp a new task, we don’t actually learn it from scratch. Instead, we use a lot of prior knowledge that we have acquired throughout our lives and experiences.

We understand about gravity and its implications. We know that if we let a cannonball and a bird feather fall from the same starting point, the cannonball will reach the ground first because of the different effect of the air resistance in both objects. We know that objects are not supposed to float in the air. We understand common sense knowledge about how the world works. You know that if your father has a child, he or she will be your sibling. We know that if we read in a paper that someone was born in the 1900s he/she is probably no longer alive because we know (by observing the world) that people don’t often live more than 120 years.

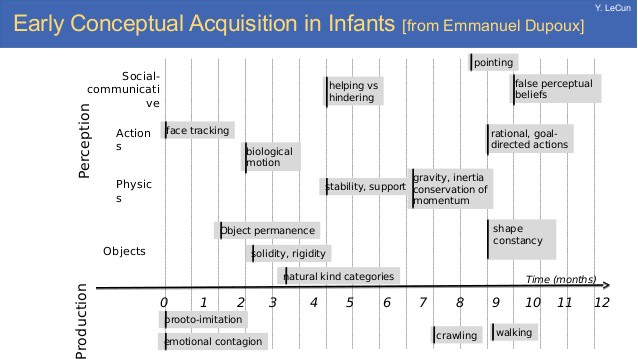

We understand causality between events and etc. And most curious, we actually learn many of these high-level concepts very early in life. Indeed, we learn concepts like gravity and inertial with only 6 to 7 months. At this age, interaction with the world is almost none!

Source: Early Conceptual Acquisition in Infants [from Emmanuel Dupoux]. Yann LeCun slides

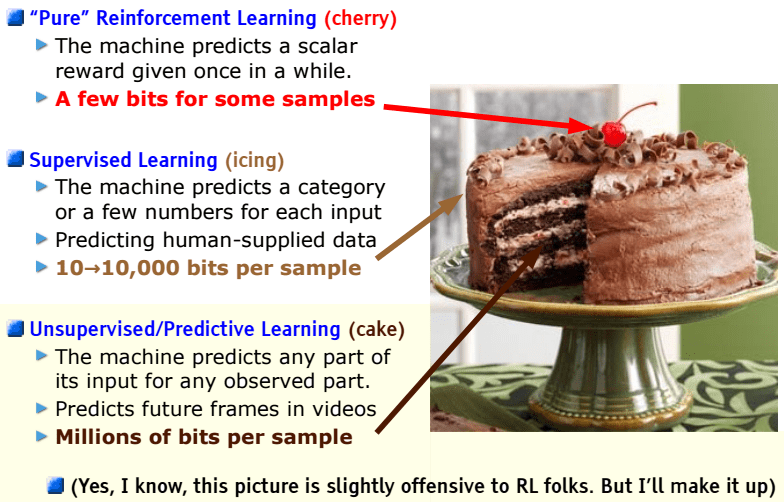

In this sense, it would not be “fair” to compare the performance of algorithms with humans — some might say. In one of his talks on self-supervised learning, Yann LeCun argues that there are at least 3 ways to get knowledge.

- Through observation

- From supervision (mostly from parents and teachers)

- From reinforcement feedback

However, if we consider a human infant as an example, interaction at that age is almost none. Nevertheless, infants manage to build an intuitive model of the physics of the world. Thus, high-level knowledge like gravity could only be learned by pure observation — At least, I haven’t seen any parents teaching physics to a 6-month baby.

Only later in life, when we master language and start going to school, supervision and interaction (with feedbacks) become more present. But more importantly, when we reach these stages of life, we already have developed a robust model world. And this might be one of the main reasons why humans are so much more data-efficient than current machines.

As LeCun puts it, reinforcement learning is like the cherry in a cake. Supervised learning is the icing and self-supervised learning is the cake!

Source: Yann LeCun slides

Self-Supervised Learning

In self-supervised learning, the system learns to predict part of its input from other parts of it input — LeCun

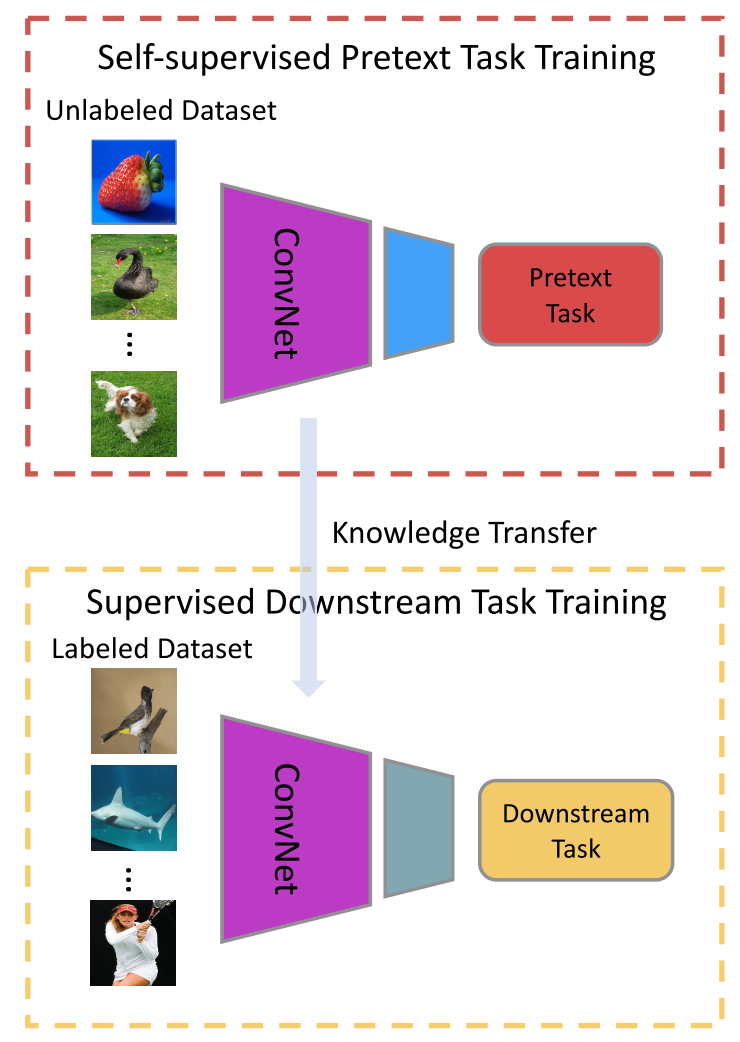

Self-supervised learning derives from unsupervised learning. It’s concerned with learning semantically meaningful features from unlabeled data. Here, we are mostly concerned with self-supervision in the context of Computer Vision.

The general strategy is to transform an unsupervised problem into a supervised task by devising a pretext task. Usually, a pretext task has a general goal. The idea is to make the network capture visual features from images or videos.

Pretext tasks and common supervised problems share some similarities. We know that supervised training requires labels. These, in turn, are usually collected with the effort of human annotators. However, there are many scenarios in which labels are either very expensive or impossible to get. Moreover, we also know that deep learning models are data-hungry by nature. As a direct result, large-scaled labeled datasets have become one of the main walls for further advancements.

Well, self-supervised learning also requires labels for the training of pretext tasks. However, there is a key difference here. The labels (or pseudo-labels) used to learn pretext tasks have a different characteristic.

In fact, for self-supervised training, the pseudo-labels are solely derived from the data attributes alone.

In other words, there is no need for human annotation. Indeed, the main difference between self and supervised learning lies in the source of the labels.

- If the labels come from human-annotators (like most datasets) it is a supervised task.

- If the labels are derived from the data, in which case we can automatically generate them, we are talking about self-supervised learning.

Recent studies have proposed many pretext tasks. Some of the most common ones include:

- Rotation

- Jigsaw puzzle

- Image Colorization

- Image inpainting

- Image/Video Generation using GANs

Check out a summary description of each pretext task here.

Credits: Self-supervised Visual Feature Learning with Deep Neural Networks: A Survey

With self-supervised training, we can pre-train models on incredibly large databases without worrying about human-labels.

In addition, there is a stubble difference between pretext and usual classification tasks. In pure classification, the network learns representations with the goal of separating the classes in the feature space. In self-supervised learning, pretext tasks usually challenge the network to learn more general concepts.

Take the image colorization pretext task as an example. In order to excel in it, the network has to learn general-purpose features that explain many characteristics of the objects in the dataset. These include the objects’ shape, their general texture, worry about light, shadows, occlusions, etc.

In short, by solving the pretext task, the network will learn semantically meaningful features that can be easily transferred to learn new problems. In other words, the goal is to learn useful representations from unlabeled data before going supervised.

Conclusion

Self-supervised learning allows us to learn good representations without using large annotated databases. Instead, we can use unlabeled data (which is abundant) and optimize pre-defined pretext tasks. We can then use these features to learn new tasks in which data is scarce.

Thanks for reading!

Cite as:

@article{

silva2020selfsupervised,

title={Self-Supervised Learning and the Quest for Reducing Labeled Data in Deep Learning},

author={Silva, Thalles Santos},

journal={https://sthalles.github.io},

year={2020}

url={https://sthalles.github.io/self-supervised-learning/}

}