Representation Learning Through Self-Prediction Task Optimization

[machine-learning deep-learning representation-learning self-supervised-learning contrastive-learning

Abstract

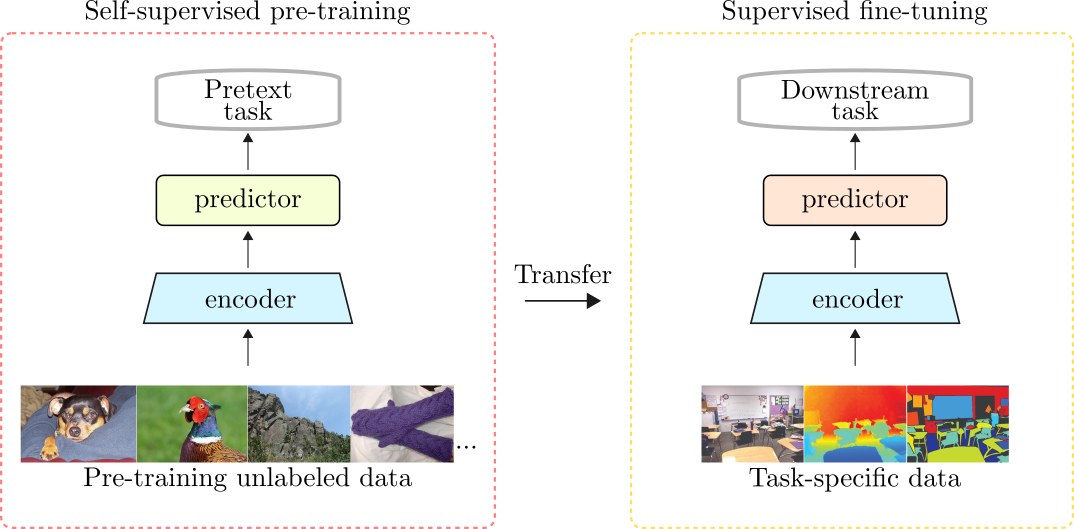

Representation learning aims to map a high-dimensional complex data point to a compact and low-dimensional representation. This low-level representation must be generalizable, i.e., it must ease the process of learning new downstream tasks to the extent that new tasks should require fewer labeled examples than it would if learning from scratch. In computer vision (CV), this process is majorly done using supervised learning. After training a sufficiently large neural network on a large corpus of annotated data, the features learned by the encoder are helpful to learn new downstream tasks in which annotated data are scarce or impossible to get. This is called transfer learning, and it applies to many other data modalities. However, there is an alternative way. Instead of pre-training the encoder using an annotated dataset on a specific task like classification, what if we could pre-train the same encoder on non-annotated data and learn similarly useful features that could provide strong priors to learn new tasks? In this way, we could use the encoder’s features to learn new tasks and achieve relatively good results without relying on enormous annotated datasets. This piece briefly reviews some influential self-supervised learning (SSL) methods for representation learning of visual features. We address methods that learn useful representations from unlabeled data by devising and optimizing self-prediction tasks (SPT). In the context of SSL, an SPT is an optimization task posed at the individual data point level. Usually, some part of the data is intentionally hidden or corrupted, and the network is challenged to predict that missing part or property of the data from the available information. Since the network only has access to some part of the data point, it needs to leverage intra-sample statistics to solve the task. These tasks are also known as pretext tasks, and they act as proxies to learn representations from unlabeled data. When optimized using such pretext tasks, a neural network can learn features that can generalize across different tasks and thus, ease the process of learning downstream tasks reducing costs, including computing time and data annotation.

Introduction

We can view SSL as a series of prediction tasks that aim to infer missing parts of the input from the partially visible context. In general, it relates to the idea of devising pretext tasks to predict an occluded portion of the data from the partially observed context. These concepts are prevalent in NLP, where we can learn word-embeddings by predicting neighboring words based on the surrounding context (Mikolov et al. 2013)1.

Researchers have proposed many self-supervised tasks to learn representations from image data. For instance, generative-based pretext tasks attempt to learn the data manifold by posing a reconstruction task on the input space to recover the original input signal from a usually corrupted input. This category includes popular methods such as variational auto-encoders (VAEs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs).

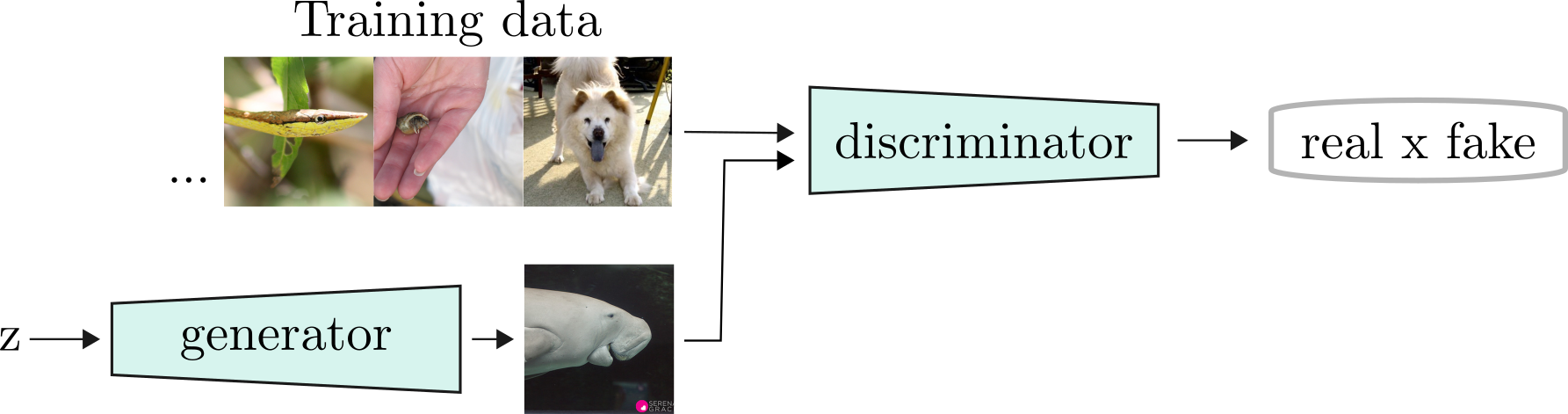

Kingma and Welling 20132 proposed a Bayesian approach to (VAEs) where the decoder generates data conditionally on a latent variable $z$ while the encoder is trained to infer the latent variable from the input. In the (GANs) setup, Figure 1, the encoder takes in the latent variable $z$ and learns to produce a data point $\tilde{x} = g(z)$ that comes from the original data distribution, where the function $g(\cdot)$ is a neural network known as a generator.

Implementations such as BiGAN (Donahue et al. 2016)3 trains an additional encoder function to invert the encoding process in order to map a data point $x$ to a latent representation $z$.

Another class of generative models attempts to predict the values of a high dimensional signal, such as an image, in an autoregressive manner. These implementations make predictions at the pixel level. Using a raster scan order, they predict the next pixel value conditioned on the values they have seen before. Examples include PixelRNN (Oord, et al. 2016)4, PixelCNN (Oord, et al. 2016)5, and ImageGPT (Chen, et al. 2020)6. Although representation learning may not be the primary objective of such methods, they all have been used as feature extractors, in a transfer learning scenario, to learn downstream tasks.

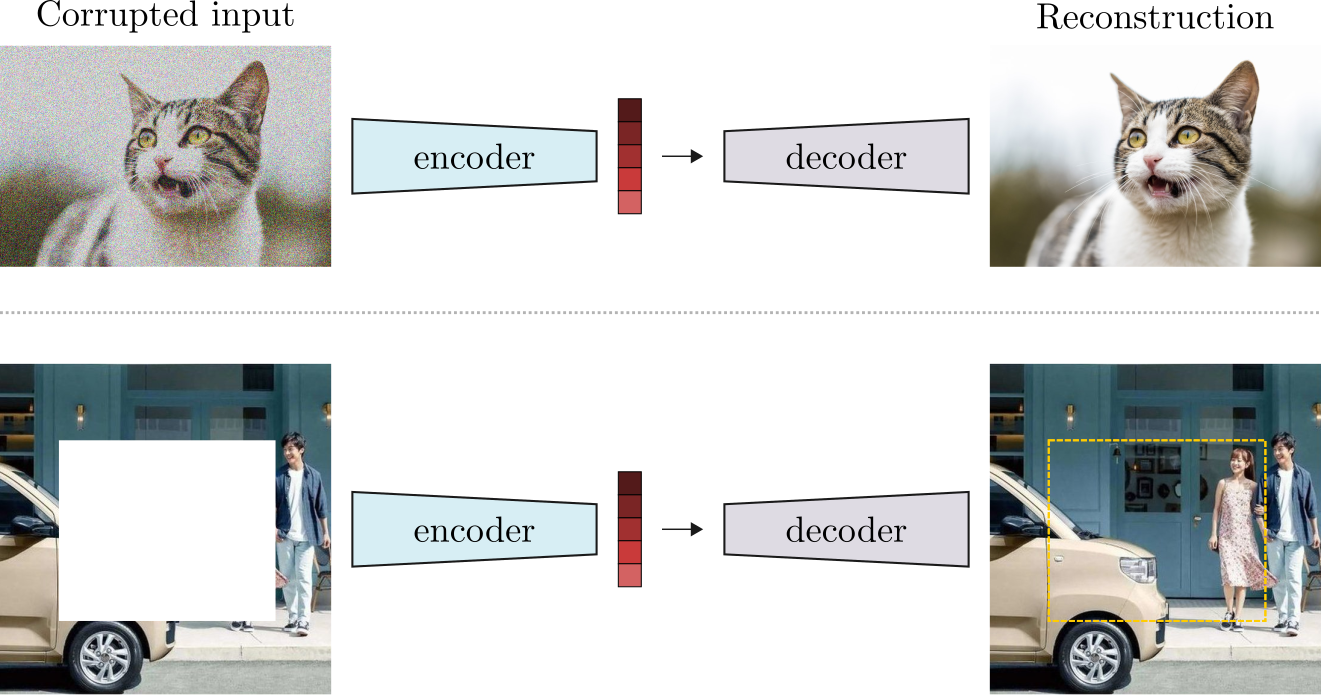

Analogous to the task of masked language modeling in natural language processing (NLP), masked prediction tasks for images include denoising autoencoders and image inpainting. Vincent, et al. 20087 proposed to learn robust representations by learning denoising autoencoders. Here, a given input image is changed by a noise distribution that corrupts randomly chosen pixel values. The network receives the noisy input and rebuilds the original image using a reconstruction loss in the image space, Figure 2 (top).

Similarly, Pathak, et al. 20168 present a generative model to learn visual features by intentionally masking a portion of the input image and challenging a deep neural network to fill in the missing regions. Besides the reconstruction loss, the system is optimized with an adversarial loss that further improves the reconstruction and the quality of the representations. Refer to Figure 2 (bottom).

The Exemplar Pretext Task

The Exemplar-CNN proposed by Dosovitskiy, et al. 20159, is an example of a self-supervised method for learning transferable representations. Built on top of the concepts presented by Malisiewicz, et al. 201610, the main idea is to devise a prediction task that treats each image (an exemplar) and variations of it as a unique surrogate class.

Each surrogate class contains randomly transformed variations of an image. These variations, also called views, are created by applying stochastic data transformations to the input image. Such transformations include cropping, scaling, color distortions, and rotations. Each set of views from the same exemplar gets assigned a unique surrogate class, and the network is optimized to correctly classify views from the same image as belonging to the same surrogate class. The exemplar pretext task is optimized using the cross-entropy loss and was trained with 32000 surrogate classes. In its time of publication, the Exemplar-CNN outperformed the current state-of-the-art (SOTA) for unsupervised learning on several popular benchmarks, including STL-10, CIFAR-10, Caltech-101, and Caltech-256.

Since there is a one-to-one correspondence between an image and a surrogate class, the exemplar pretext task becomes challenging to scale to enormous datasets such as the ImageNet with 1.3 million records. To address this limitation, Doersch and Zisserman 201711 proposed to use the Triplet Loss function (Schroff, et al. 2015)12 as a way to scale the task to larger datasets. In short, the exemplar pretext task is a framework that aims to train a classifier to distinguish between different input samples. This strategy forces the network to learn representations that are invariant to the set of data augmentations used to create the views. Moreover, the concept of creating different views by using heavy data augmentation, now popularly referred to as instance discrimination, is one of the foundations of current SSL methods.

The Relative Patch Prediction Pretext Task

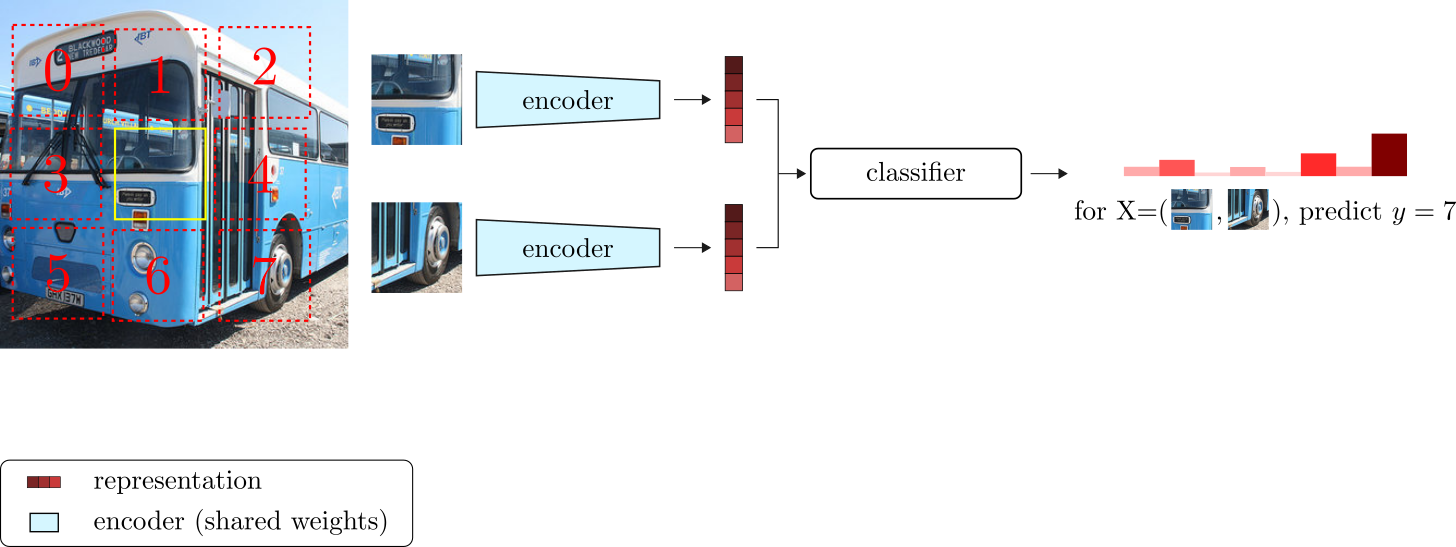

A contemporary work by Doersch, et al. 201613 proposed the relative patch prediction pretext task. This method introduces the idea of training a neural network to predict the relative positions of patches in an image. The learning framework is elegantly simple. First, a random patch is extracted from an image and used as the center relative position. From the center patch, we can extract 1 of 8 other patches (in a grid fashion) such that the relative position between the central patch and one of the surrounding patches is deterministic. Given a pair of patches as input, the network is trained to learn the relative position of the central patch with respect to its neighbor. Figure 3 depicts the training architecture.

The goal is to learn a visual representation vector (an embedding) for each patch, such that patches that share visual semantic similarities also have similar embeddings.

The relative patch prediction pretext task is optimized as an 8-way classification problem using the cross-entropy loss. The feature representations learned through the relative patch pretext task achieved SOTA performance on the Pascal VOC detection dataset. Moreover, different from the exemplar pretext task, the relative patch prediction task is much more scalable. For this reason, this work is considered one of the first successful large-scale SSL methods.

The Jigsaw Puzzle Pretext Task

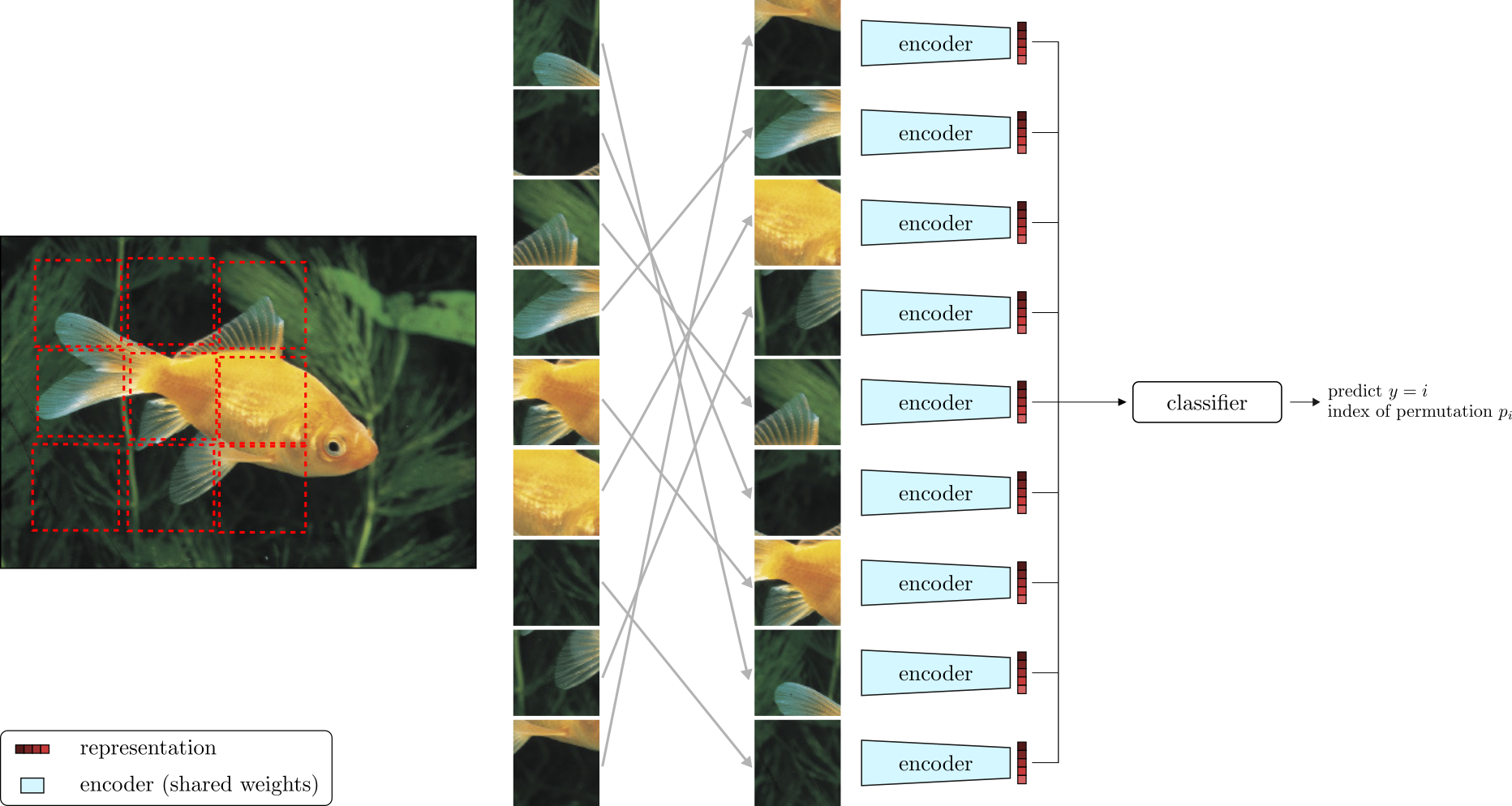

Similar to the relative patch prediction pretext task, Noroozi and Favaro 201714 proposed a pretext task to learn visual representations by solving jigsaw puzzles. From a single image, the formulation involves sampling nine crops (in a grid pattern) that are shuffled using a randomly chosen permutation $p_i$ sampled from a set of permutations $\bar{P}$. The network receives the patches in random order, and the pretext task is to predict which permutation was used to rearrange the image patches.

Since the number of possible permutations follows a factorial growth, the authors used a small subset of 1000 handpicked permutations. The subset of 1000 permutations is chosen based on their Hamming distances. Specifically, as the average Hamming distance between the permutations grows, the pretext task becomes harder to solve, and as a consequence, the network learns better representations.

Intuitively, generating a maximal Hamming distance permutation set avoids cases where many permutations are very similar to one another, which would ease the challenge imposed by the pretext task. Fig~\ref{fig:jigsawPuzzle} depicts the jigsaw puzzle ConvNet architecture.

The jigsaw puzzle pretext task is formulated as a 1000-way classification task, optimized using the cross-entropy loss. Training classification and detection algorithms on top of the fixed representations leaned from the jigsaw pretext task showed advantages over the previous methods.

The Rotation Prediction Pretext Task

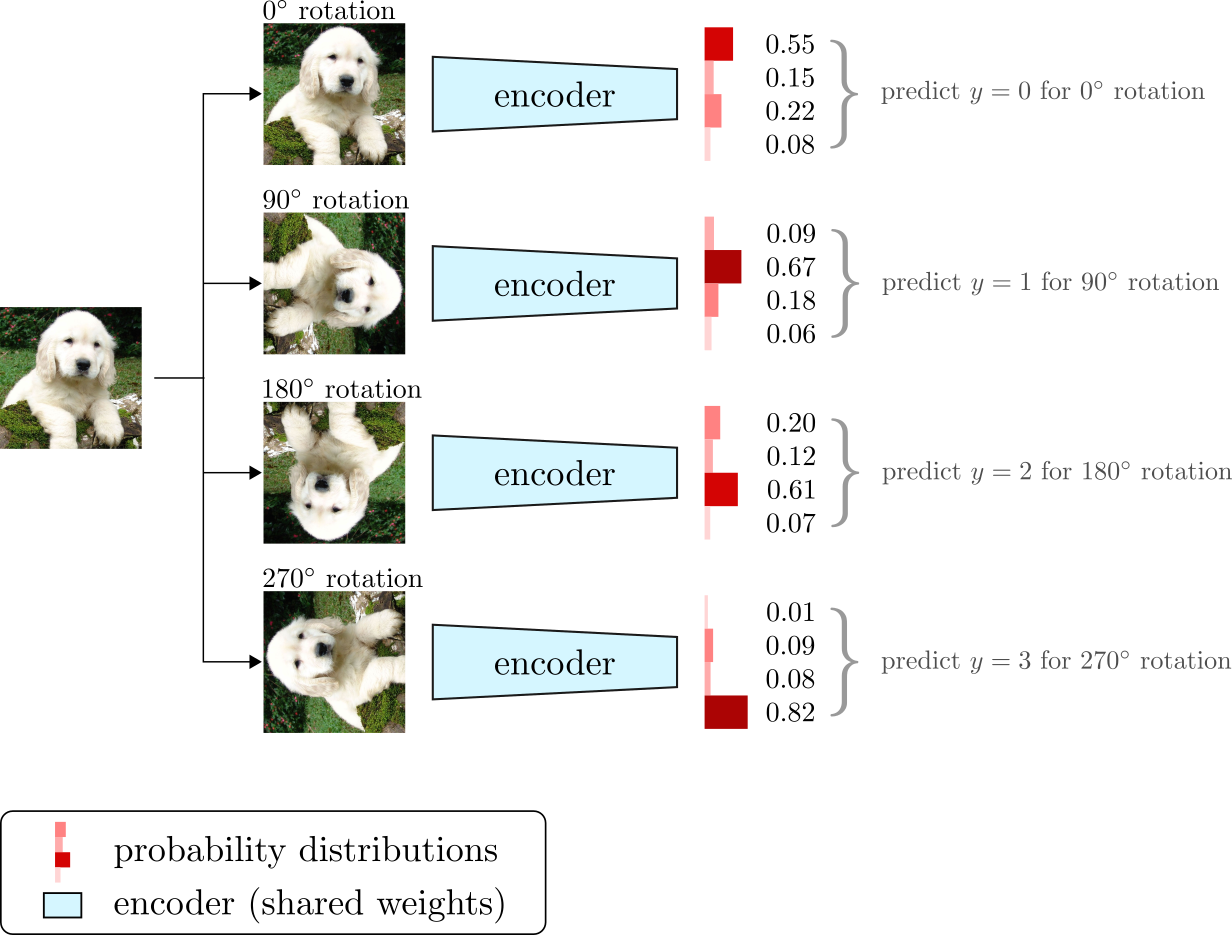

Gidaris et al. 201815 presented another simple and yet powerful self-supervised pretext task. The rotation prediction pretext task is a method to learn unsupervised visual representations by predicting which rotation angle was applied to an input image. For an input image $x$ and a rotation angle $\beta$ (randomly picked from a set of predefined values), the image $x$ is rotated by an angle $\beta$ and fed as input to a ConvNet. Then, the pretext task is to predict which of the valid rotation angles was used to transform the input image.

The rotation prediction pretext task is designed as a 4-way classification problem with rotation angles taken from the set ${0^\circ, 90^\circ, 180^\circ, 270^\circ}$. The framework is depicted in Figure 5. Despite its simplicity, the rotation pretext task achieved SOTA performance on various unsupervised feature learning benchmarks, including classification on ImageNet, and transfer learning on PASCAL VOC.

Limitations of Pretext Task Optimization

One might ask why solving jigsaw puzzles or predicting rotation angles makes the network learn useful representations. Although the answer to this question is still open, helpful intuitions hint at why optimizing these pretext tasks results in learning useful visual semantic structures from data. To excel in a task such as relative patch prediction or jigsaw puzzle, the network needs to learn how different object parts relate to one another. Moreover, both tasks force the network to learn spatial context structure among the image patches. In other words, these tasks require the network to learn features that encode spatial reasoning.

Similarly, predicting random rotations drives the network to learn orientation concepts about objects. These concepts are well known and straightforward to humans but are very difficult to be encoded in computer systems. Such notions might include learning that trees grow upwards (instead of side-ways or downward) or that a person’s head should be on top of the shoulders, not below them. In the same way, for contextual prediction tasks such as jigsaw and relative patch prediction, the network must learn spatial consistency features so that it can predict that a patch containing the nose of a living creature should go on top of the patch containing its mouth.

Another important characteristic of these pretext tasks is that they usually use the same loss functions of regular supervised training. In fact, from an optimization standpoint, the only substantial difference between these self-supervised methods and regular classification algorithms is the source of labels. While training a classifier often require human annotations, SSL extracts the supervisory signal from the data.

The idea of optimizing pretext tasks that extract training signals from the data has gained much traction in computer vision (CV). It has been applied to different domains, including video and audio-based applications. Despite its potential, however, when comparing supervised and self-supervised-based representations for learning downstream tasks, early attempts to learn via self-prediction were still far behind.

Moreover, devising pretext tasks pose the disadvantage of creating the task itself. Indeed, creating such pretext tasks can be seen as a handcrafted procedure with no guarantees that optimizing for a given pretext task will push the network to learn semantically meaningful features that can transfer well to other tasks. Take the rotation prediction pretext task as an example. One would think that increasing the set of possible angles (from 4 to 8) would increase the quality of the final representations because the pretext task is now more challenging. However, an ablation study using multiples of 45-degree rotation angles (from $0^\circ$ to $315^\circ$) instead of multiples of 90-degrees showed that the overall feature performance actually decreased.

Another significant drawback of these manually created self-supervised pretext tasks is that optimizing them makes the network learn visual representations that covary with the choice of pretext task (Misra et al. 2020)16. Moreover, Kolesnikov et al. 202017 have shown that the quality of visual representations learned via pretext task optimization is very sensitive to the choice of ConvNet architecture. Put it differently, the choices of network architecture and pretext tasks seem to influence the quality of the final visual representation.

Driven by these findings, current methods (He et al. 2018)18 for self-supervised visual representation learning seem to have deviated from optimizing pretext tasks to adopt a common framework based on contrastive learning algorithms (Hadsell et al. 2005)19 with join-embedding architectures. In essence, contrastive methods learn visual representations in the embedding space by approximating pairs of representations of the same concept.

This family of methods optimizes representations in the feature space and avoids the computation burden of reconstructing the input signal. Moreover, recent contrastive and non-contrastive methods have achieved SOTA performance surpassing both self-supervised pretext tasks and latent variable models in nearly all representation learning benchmarks.

The following article will go over some of the most influential contrastive and non-contrastive methods for visual representation learning, one of the hottest areas in computer vision.

Thanks for reading!

Cite as:

@article{

silva2022selfprediction,

title={Representation Learning Through Self-Prediction Task Optimization},

author={Silva, Thalles Santos},

journal={https://sthalles.github.io},

year={2022}

url={https://sthalles.github.io/self-supervised-pretext-task-learning/}

}

References

-

Mikolov, Tomas, et al. “Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781 (2013). ↩

-

Kingma, Diederik P., and Max Welling. “Auto-encoding variational bayes.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114 (2013). ↩

-

Donahue, Jeff, Philipp Krähenbühl, and Trevor Darrell. “Adversarial feature learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1605.09782 (2016). ↩

-

Van Oord, Aaron, Nal Kalchbrenner, and Koray Kavukcuoglu. “Pixel recurrent neural networks.” International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2016. ↩

-

Van den Oord, Aaron, et al. “Conditional image generation with pixelcnn decoders.” Advances in neural information processing systems 29 (2016). ↩

-

Chen, Mark, et al. “Generative pretraining from pixels.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2020. ↩

-

Vincent, Pascal, et al. “Extracting and composing robust features with denoising autoencoders.” Proceedings of the 25th international conference on Machine learning. 2008. ↩

-

Pathak, Deepak, et al. “Context encoders: Feature learning by inpainting.” Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2016. ↩

-

Dosovitskiy, Alexey, et al. “Discriminative unsupervised feature learning with convolutional neural networks.” Advances in neural information processing systems 27 (2014). ↩

-

Malisiewicz, Tomasz, Abhinav Gupta, and Alexei A. Efros. “Ensemble of exemplar-svms for object detection and beyond.” 2011 International conference on computer vision. IEEE, 2011. ↩

-

Doersch, Carl, and Andrew Zisserman. “Multi-task self-supervised visual learning.” Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. 2017. ↩

-

Schroff, Florian, Dmitry Kalenichenko, and James Philbin. “Facenet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering.” Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2015. ↩

-

Doersch, Carl, Abhinav Gupta, and Alexei A. Efros. “Unsupervised visual representation learning by context prediction.” Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 2015. ↩

-

Noroozi, Mehdi, and Paolo Favaro. “Unsupervised learning of visual representations by solving jigsaw puzzles.” European conference on computer vision. Springer, Cham, 2016. ↩

-

Gidaris, Spyros, Praveer Singh, and Nikos Komodakis. “Unsupervised representation learning by predicting image rotations.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.07728 (2018). ↩

-

Misra, Ishan, and Laurens van der Maaten. “Self-supervised learning of pretext-invariant representations.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2020. ↩

-

Kolesnikov, Alexander, Xiaohua Zhai, and Lucas Beyer. “Revisiting self-supervised visual representation learning.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2019. ↩

-

He, Kaiming, et al. “Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2020. ↩

-

Hadsell, Raia, Sumit Chopra, and Yann LeCun. “Dimensionality reduction by learning an invariant mapping.” 2006 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’06). Vol. 2. IEEE, 2006. ↩